Folk Music Regions Explorer

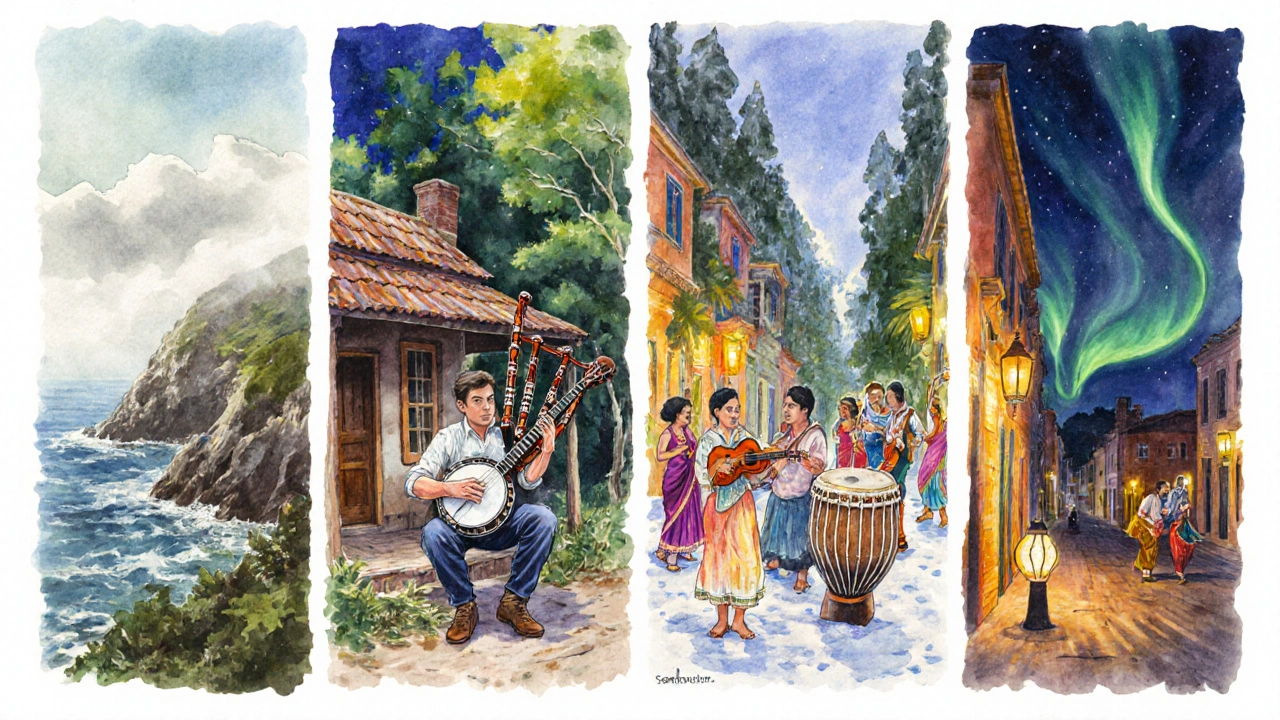

Discover how geography shapes the sound and stories of folk music from around the world.

Celtic

Fiddle, tin whistle, uilleann pipes

Themes: Mythology, seafaring, love

Artists: Planxty Andy McKee, The Chieftains

Appalachian

Banjo, acoustic guitar, mandolin

Themes: Work labor, migration, religious faith

Artists: Doc Watson, The Carter Family

Afro-Cuban

Claves, bongos, tres

Themes: Community celebration, social justice

Artists: Buena Vista Social Club, Celia Cruz (early work)

Nordic

Hardanger fiddle, nyckelharpa

Themes: Nature, winter folklore, sea voyages

Artists: Mari Kaasinen, Garmarna

Indian

Sarangi, dholak, bansuri

Themes: Mythic epics, village festivals, love

Artists: Ravi Shankar (folk collaborations), Gurdas Maan

Did You Know?

Folk music is more than just songs-it's a living archive of community experiences. Each tradition carries unique instruments and themes that reflect local life and history.

Try listening to one track from each region to understand how different sounds tell similar stories about everyday life and culture.

Folk music is a living archive of community life, passed down through generations by voice, string, and rhythm. It captures everyday joys, struggles, and rituals, turning ordinary moments into shared stories that echo across continents.

What Makes Folk Music Different?

At its core, folk music is rooted in the people who create it. Unlike commercial pop, which is often produced for mass appeal, folk songs emerge from local experiences-farm work, weddings, protests, hearth gatherings. These songs rely on simple structures, repetitive melodies, and lyrics that speak directly to daily life.

Because the focus is on community, the genre thrives on oral tradition. Musicians learn by listening and imitating, not by reading sheet music. This oral transmission keeps the music fluid, allowing each performer to add a personal touch while preserving the song’s heart.

Storytelling as a Musical Tool

Storytelling and music are inseparable in folk cultures. A typical verse might recount a historic battle, a love lost at sea, or a harvest celebration. The narrative sketched in a few lines can convey generations of collective memory. For example, the Irish ballad “The Fields of Athenry” tells a vivid tale of famine and exile, reminding listeners of a painful era while still resonating with modern audiences.

When a song tells a story, it becomes a portable history lesson. Listeners who might never read a textbook still absorb the cultural lessons embedded in the melody.

Instruments That Define the Sound

Acoustic guitar provides a warm, resonant backbone, perfect for accompanying vocals. Its portability makes it a staple at house parties and campfires.

Banjo adds a bright, percussive twang that’s iconic in Appalachian and African‑American folk traditions. Its five‑string design allows rapid rolls that mimic the cadence of work songs.

Fiddle (or violin) brings soaring melodies that can mimic the cries of wolves or the rustle of leaves, and it’s central to Celtic, Nordic, and many Eastern European styles.

Other regional instruments-like the Australian didgeridoo, the Brazilian berimbau, or the Indian sarangi-infuse local flavor, yet they all share a common goal: to amplify community voices.

Regional Flavors: A Quick Comparison

| Region | Primary Instruments | Typical Themes | Notable Artists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Celtic | Fiddle, tin whistle, uilleann pipes | Mythology, seafaring, love | PlanxtyAndyMcKee, The Chieftains |

| Appalachian | Banjo, acoustic guitar, mandolin | Work labor, migration, religious faith | DocWatson, The Carter Family |

| Afro‑Cuban | Claves, bongos, tres | Community celebration, social justice | BuenaVistaSocial Club, CeliaCruz (early work) |

| Nordic | Hardanger fiddle, nyckelharpa | Nature, winter folklore, sea voyages | MariKaasinen, Garmarna |

| Indian | Sarangi, dholak, bansuri | Mythic epics, village festivals, love | RaviShankar (folk collaborations), GurdasMaan |

These snapshots reveal how geography shapes the instrument palette, lyrical focus, and iconic voices, yet the underlying purpose remains the same: to give a soundtrack to everyday life.

Folk Music in Modern Life

Even in the digital age, folk music finds new homes. Indie artists remix traditional ballads with electronic beats, while social media platforms let remote villages share field recordings worldwide. The folk festival circuit-think Newport Folk Festival or the Melbourne Folk Festival-acts as a yearly gathering where novices and legends swap songs under open skies.

Revival movements, such as the 1960s American folk boom or today's “neo‑folklore” trend, breathe fresh relevance into old tunes. Musicians like Ella Hooper and Holly Near reinterpret protest songs for climate activism, proving that the genre’s message of community can power contemporary causes.

Beyond entertainment, folk music serves therapeutic purposes. Therapists use simple melodies and communal singing to lower anxiety, improve speech in stroke patients, and foster cultural pride among diaspora youth.

Preserving the Heritage

Preservation today blends archive labs with community participation. Organizations digitize field recordings, tag them with metadata, and store them in open‑access libraries. Yet the most robust safeguard remains the living tradition: elders teaching youngsters at kitchen tables, community centers, and online workshops.

Technology aids this effort. Mobile apps let users upload verses, attach location data, and connect with other singers worldwide. These crowdsourced databases act as a modern oral tradition, ensuring songs never fade even if the original community disperses.

How to Dive Into Folk Music Yourself

- Start with a local playlist. Look for regional compilations on streaming services-search “Celtic folk” or “Appalachian roots”.

- Pick up a simple instrument. An acoustic guitar or a beginner’s banjo can be learned in a few weeks using free YouTube tutorials.

- Attend a live folk event. Small venues often host open‑mic nights where anyone can join in.

- Explore field recordings. The Library of Congress, the British Library Sound Archive, and the Australian National Folklore Collection host thousands of historic tracks.

- Share a song. Record yourself singing a verse and post it on a community forum; you’ll discover others eager to add their harmonies.

Each step brings you closer to the soundtrack that has narrated human life for centuries.

Key Takeaways

- Folk music is a community‑driven archive that turns daily experiences into shared melodies.

- Storytelling, simple instrumentations, and oral transmission are the genre’s hallmarks.

- Regional styles differ in instruments and themes but all aim to preserve cultural identity.

- Modern revivals, festivals, and digital archives keep the tradition vibrant today.

- Anyone can join the tradition by listening, learning an instrument, and sharing songs.

Frequently Asked Questions

What defines a song as folk music?

A folk song typically originates from a specific community, uses simple melodic structures, and conveys everyday stories, cultural values, or historical events. It’s passed down orally rather than through formal publishing.

Can modern pop songs be considered folk?

Only if they adopt the folk process-community‑based creation, acoustic instrumentation, and storytelling rooted in local experience. Many indie artists blend folk elements with pop, creating a hybrid style.

How do I find authentic folk recordings?

Look for archives from national libraries (e.g., Library of Congress Folk Archive), reputable world‑music labels, and curated playlists on streaming platforms that reference field recordings.

Why are folk festivals important?

Festivals gather diverse musicians, provide a stage for oral transmission, and create a communal space where songs can be shared, learned, and revived in real time.

Is folk music useful for therapy?

Yes. Simple rhythms and group singing can lower stress, improve speech recovery, and strengthen cultural identity, especially in community‑based therapeutic programs.